Dangerous Waters

But not for the first time

I had planned to share an essay today about the future of the presidency and the Supreme Court. I also had my usual book selections and some really fun Making the Presidency updates. But those didn’t feel quite right. So I think, for the first time in five years, I will send out two posts in one month. I’ll send out my planned post on August 1 with all of the normal features.

For today, I want to share my thoughts on the history of assassinations and political violence more broadly. I should stress that this situation is unfolding fairly rapidly and there is a great deal we don’t know - including why this happened. Accordingly, I’m actually going to say very little about Saturday’s events. Instead, I want to look at everything around it.

A History of Assassinations

There is a long history of assassinations and attempts in US history, long before we even had a president. In June 1776, a plot to assassinate George Washington was discovered and foiled by the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies, led by John Jay. During John Adams’s presidency, political violence was ever-present. Newspaper editors were beaten, mobs clashed in the streets, and anonymous threats were delivered to the President’s House.

The first assassination attempt against a president (that I’m aware of) occurred in 1835, when Richard Lawrence attempted to fire two pistols at Andrew Jackson. His pistols misfired and Jackson used his cane to severely beat Lawrence.

There have been tons of other attempts or threats since then, many of which were thwarted over the years by law enforcement. I want to focus on two periods of time that are particularly instructive.

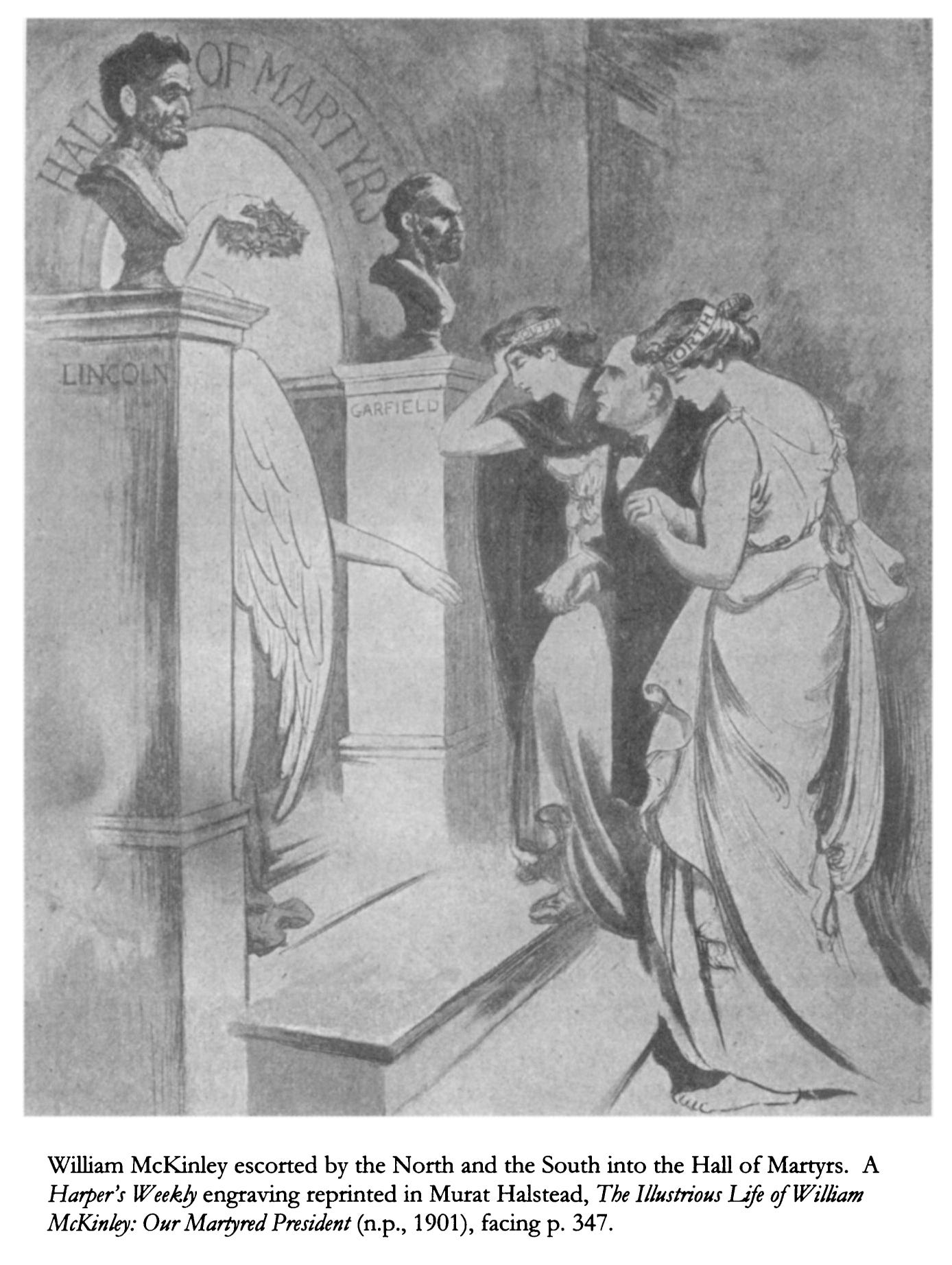

On April 15, 1865, Robert Lincoln was 22 years old. He was visiting his family at the White House when his father, Abraham Lincoln, was assassinated. Sixteen years later, he was serving as secretary of war. On July 2, 1881, he accompanied President James Garfield to the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, where he witnessed Charles Guiteau shoot the president. On September 6, 1901, Lincoln was the president of the Pullman Palace Car Company and attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. He wasn’t in the room, but he was nearby when President William McKinley was assassinated.

Three presidential assassinations in less than forty years. Many Americans, like Robert Lincoln, had lived through all three. And just a decade later, Theodore Roosevelt survived another assassination attempt. I cannot imagine how profoundly destabilizing those violent deaths felt for Americans.

McKinley’s assassination prompted Congress to request full time Secret Service protection for presidents. Prior to 1902, protection had been sporadic, depending on the moment and the president.

The 1960s witnessed another wave of political assassinations, including Medgar Evers (1963), John F. Kennedy (1963), Malcolm X (1965), Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (1968), and Robert F. Kennedy (1968).

In response, Congress passed a series of laws extending presidential protection to first families, former presidents, and ultimately major party candidates.

What Assassinations Reveal about the Moment

While each decade of American history has its own peculiarities, there are a few similarities between the post-Civil War period and the 1960s: robust bottom-up reform movements, racial divisions and violence, social upheaval after major military conflicts, generational turnover in political leadership, xenophobia, battles over civil rights, intraparty divisions as well as interparty fighting, and geographical shifts in party membership.

These conditions produced increased partisan tensions, virulent rhetoric, and heightened convictions that radical means were justified to preserve their way of life or protect the nation as they saw it.

Political violence then starts in small ways. Threats to the press, seemingly random assaults or attacks on voting places, election officials, or law enforcement officers, or destruction of property (i.e. graffiti, smashing windows, or burning crosses on a front lawn) are typical first spasms of political violence. These tend to escalate into more organized violence or escalate into more fatal attacks (like assassinations). Once violent speech and violent acts are in the political bloodstream they are rarely isolated incidents. Political violence tends to break out in clusters.

These conditions might sound familiar. We have spent the last 10-15 years squabbling over immigration, civil rights, and various reforms. Xenophobia regularly rears its ugly head. Voting constituencies are shifting in dramatic fashion, while many elder statesmen are resisting calls for generational turnover. The parties are weak, which has led to increased radicalism, animosity in political rhetoric, and a decline in compromise. And guns are more available than ever.

Political violence didn’t spring out of nowhere on Saturday. Representatives Gabby Giffords and Steve Scalise were both the victims of shootings. Bombs were sent (and thankfully detected) to the Obamas, Clintons, and more. Death threats and pipe bombs were sent to major newsrooms. Threats against election workers are on the rise. And, of course, the insurrection on January 6, 2021 was political violence on a grand scale.

After the quick and decisive crackdown on those involved in the fighting at the Capitol, many experts, including academics, law enforcement officers, and astute observers have predicted that large group, organized violence like we saw on January 6 was less likely in the near future. Instead, we should brace ourselves for lone acts of violence—like assassinations.

What’s Next

As I often say on television or radio when asked, historians are notoriously terrible future predictors, so I will make no wager about what comes next. But based on historical precedents, I see a few possible outcomes.

The assassination attempt on Theodore Roosevelt did little to change the 1912 election. He continued his campaign but came in second. Roosevelt was still quite popular when he decided to mount a third party campaign and perhaps the assassination attempt increased that popularity, but not enough to affect the electoral college outcome.

Similarly, I’m not sure the 1981 attempt on Ronald Reagan changed history all that dramatically. Some reports suggest the shooting gave Reagan a second honeymoon period and the administration a fresh start. Others suggest the brush with death convinced Reagan to reduce the likelihood of nuclear war, but I’m not sure how you prove that counterfactual.

Alternatively, many assassinations, including that of Lincoln, Garfield, and RFK, probably changed the course of history. Perhaps the difference is whether the president or candidate survives. It’s not yet clear how the attempt on Mr. Trump will affect future events.

More broadly, these shocking events can affect society in two ways. Either, it is a sobering moment when leaders of all stripes are chastened and put aside their fiercest criticisms of the other party to pursue unity. In 1912, the other candidates paused their campaigns out of respect for Roosevelt. Alternatively, the shooting can ratchet up the tensions, sparking a cycle of vengeance and retribution.

Much depends on the response of those in power, whether it be political office or just a big platform. They must take a beat before rushing to snap judgments, urge calm, discourage further violence, and avoid fear mongering. As I said many times over the weekend, I hope our better angels prevail but I’m not holding my breath. Hang in there.

I often wonder about the United States had we not lost Garfield.

The Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies is a new one for me. I appreciate how you pull current events into context by showing where we've been. I think you were autocorrected, as it was Medgar Evers. Thanks for the bonus thoughts!